Civil Society Foresight Observatory Weeknote 2

Developing a taxonomy of foresight

As we move into our third week of work, we are still heavily in the planning stage. We are also beginning to see how this project might develop and what its useful outputs or tools might be. For us, a major point is that as a foresight observatory we don’t replicate or reproduce work that has already been done — there is a lot of existing work. We’ve been asking how we can usefully knit this together and present information in a clear way. So the next phase of investigation is not only surveying foresight practice happening within and outside of civil society but it’s also about understanding how we collate data, and how we make this usable. Ultimately, in the future (no pun intended), the observatory should help civil society organisations integrate better ways of working with foresight.

This week, while grappling with the issue of moulding the observatory into a shape that works, we have come across a few points which we are exploring in our literature review, and hope to delve deeper into through interviews with stakeholders.

We think that foresight is excessively top down and that we should be moving towards a plurality of futures, where more people can have a say in producing and participating in the creation of multiple futures. In order to start collecting evidence, we want to flesh out our argument. Historically, foresight practices have emerged from the corporate world, and are heavily used for the development of technological futures. The outcome of this history is that our current understanding of the process involved in constructing futures does not yet match the ease with which we can imagine innovations and hence produce ‘futures’. As Selin puts it:

“Grasping complexity over the long term and accounting for the ongoing myriad of interactions between values, machines and regimes has proven daunting for the social sciences.” (Selin, 2008).

So it is not only important for us to find a way to capture what foresight is happening, but to find a way to create a taxonomy that allows for better understanding of the process.

Limitations

Exploring the process illuminates limitations. Foresight practices attempt to tackle the problem of the growing speed of development in modern societies, while addressing future uncertainty. Growing out of the work of future studies scholars such as (Bell, 1997), techniques such as technology assessment are used by foresight practitioners to gauge the future, utilising anticipatory knowledge. The challenge here is that they mould certain outputs, through fixed inputs; the linear and temporal nature of knowledge (and data) becomes apparent, it is contextual and time dependent. These techniques can falsely bring order to disorder, and in the process smooth out complexity in unfair or discriminatory ways.

An alternative framing of foresight is one of understanding stories and differing interpretations of how the world could be. In this way, foresight is used to understand, “explicit and implicit stories…circulated to cope with future known and unknown” (Selin 2008). Tacit knowledge plays a role in creating stories using interpretive frameworks, like an ontology for experience and perception. Although such methods aim towards greater plurality, they are not without challenges. There has been some discussion of how foresight practices allow examination of these stories, and how they act to legitimise, inspire and construct emerging socio-technical futures. Again, delving into the process of such methods will allow us to uncover any implicit biases.

‘Future’ visions of politics, economics, technology and society, have been investigated from a number of perspectives. The range of approaches to understanding the future encompasses many of the debates that scholars of Science and Technology Studies (STS) have investigated for decades. These include debates around legitimation of knowledge and expertise, power relations and boundary work, as well as social construction of scientific knowledge and technological determinism. The term “sociology of the future” has been used (e.g. Bell & Mau 1971) to describe the emerging field of study, which seeks to understand future consciousness by drawing on a range of STS and the practice of foresight.

Another emerging domain is that of speculative thought, which focuses on developing methods which begin to remove the bias seen in techniques that heavily determine the inputs and data which are included in foresight. However, such techniques are limited in the applicability of their work because of the difficulty in translating their theoretical underpinnings into practice. This translational challenge is evident in the difficulty of realising ‘underdetermined values’ in practice (Stengers 2010, Michael et al. 2015). It is impractical to develop speculative approaches that are completely underdetermined and oblique, since it is not possible to understand all the factors that could lead to an outcome being influenced by a pre-determined thought, action or stimulus. Such theoretical challenges need to be overcome in order to achieve the potential to advance methods and allow engagement with ‘issues at stake’ in society.

Plurality

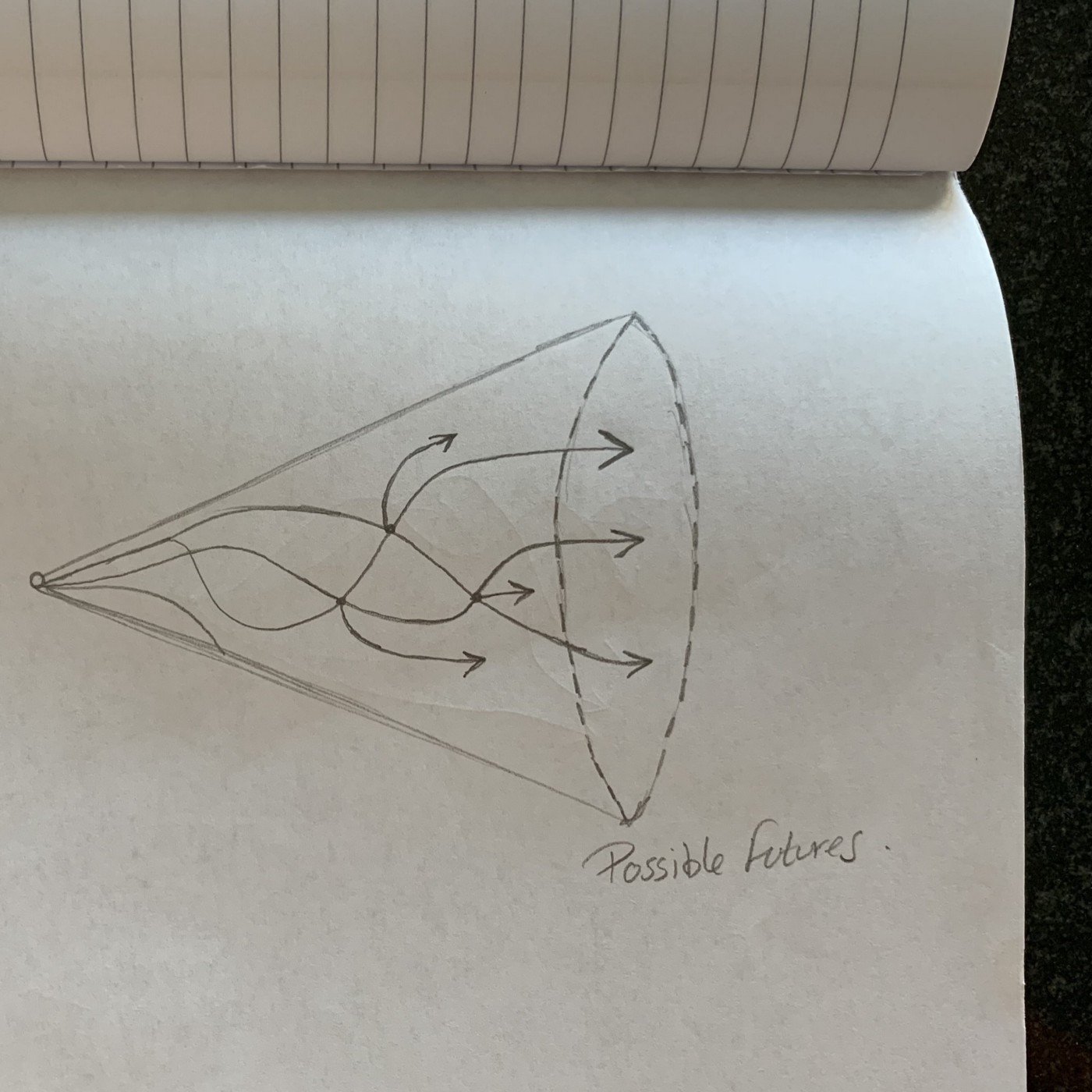

The challenge is that often only ’probable’ futures play out, a narrow set of ideas that fall within the centre of the ‘future cone’. If we could move away from the idea that foresight techniques should narrow down from many ideas to a few, then we could open the cone of the ‘probable’ to encompass many divergent ideas about the future.

Can we move away from the narrow range of ‘probable’ futures to one that encompasses more ideas?

To a futures cone where there are multiple converging possible future.

From our research this week, it is apparent that foresight is a contested domain, and our role as an observatory is to bring together the most relevant and salient thinking in the context of civil society. We also have a duty to show reflexivity; if we decide to champion methods and ideas that are ‘underdetermined’ then we need to make sure our own methods and ways of working reflect these values too. The next step is to start to think about developing a taxonomy with the information we are uncovering; thinking about the ways in which we can record methods, but also reflect on the processes these employ in the most constructive ways.