Jump to the Policy Recommendations | Research Findings

Can Innovation Places Make Good Places to Live and Work?

Rachel Coldicutt OBE

13 September 2024

With thanks to Dominique Barron, Noortje Marres and Alex Taylor for edits and suggestions.

The benefits of place-based innovation for the people who live and work in Innovation Places, such as test beds and pilot zones, are under-realised. As the new Government reconsiders the role of innovation in delivering mission-driven government, it is time to reconsider how place-based innovation funding is managed, delivered and measured.

This blog post draws together findings from the AI in the Street pilot to show how few of the societal benefits of place-based innovation are actually realised in place, and makes the case that delivering mission-driven change relies on a mixed model of innovation funding, measurement, and management — one that among others draws on local expertise and potential to build capabilities and ensure the social and economic benefits of innovation come to fruition in the places where they are tested and developed.

Better places to live and work for everyone

Innovation changes places in both direct and indirect ways.

From job creation and its spillovers to 5G lamp posts and facial recognition cameras, the impacts that technologies create and leave behind are many and varied.

Innovation policymakers, however, do not tend to prioritise the measurement of the direct social and economic impacts of innovation in local places. Instead, R&D is considered largely at national and global scales and in the context of GDP and global-facing research leadership, meaning that the impacts of place-based innovation become, effectively, divorced from place.

The findings collected on this website from the AI in the Street pilot draw together some of the impacts that innovation has in the places it is rolled out. This 6-month project, in which researchers in five cities worked with community partners and artists to situate public engagement with AI in the streets, examined the impacts of innovation from the perspectives of the people who live and work there. These impacts are diffuse and include changes to the ways people relate to one another in public spaces; opportunities for navigation and mobility; levels of trust and understanding; and access to economic opportunities.

Given the reprioritisation of public spending and the urgency of refocusing on delivering growth for the whole of the UK, this seems like an excellent moment to re-appraise the UK’s approach to place-based innovation funding. Public investment in R&D can and should have positive direct impacts on people’s standards of living and quality of life. In addition to the achievement of big social missions, place-based innovation has a role to play in building better places to live and work for everyone.

As such, we suggest the following three areas are ripe for further investigation and research in the coming months, as Government reassesses the role of UKRI as a mechanism for delivering its missions.

Participatory assessment — what is the role of communities, residents, and workers in assessing the impacts of innovation, and guiding its implementation through evaluatory frameworks?

Stewardship — what should “innovation planning” look like and can innovation in places learn from and be integrated into existing town-planning activities?

Funding — what kind of innovation funding would have a more direct impact on quality of life and economic opportunities in places, and how might this be measured?

What is the job of innovation?

The relationship of innovation to people and place influences not only the infrastructure and amenities, but also the lived experience — what Richard Sennet calls the cité, the character and consciousness of a place, that plays a vital role in its communal livability. [1] While innovation is often measured by its straightforward economic impacts or via countable artefacts such as patents registered or research papers cited, AI in the Street tells some of the stories of people in place and the experiences they have there. It shows what it is like to live and work alongside innovation, and highlights some of the factors that can stop place-based innovation realising universal benefits.

The new Government has refocussed the role of science, innovation, and technology in the UK to:

Accelerate innovation, investment and productivity through world-class science, ensure that new and existing technologies are safely developed and deployed across the UK and drive forward a modern digital government for the benefit of its citizens.

There are indications that UKRI’s strategy is also about to shift and will include “greater emphasis on using research and development to deliver major government initiatives, such as its five missions, which includes kickstarting economic growth”.

Currently, UKRI’s commitment to “world-class impacts” prioritises putting “the UK at the forefront of tomorrow’s technologies and the industries of the future”, and does not explicitly address the opportunities or challenges this might create for the places in which breakthroughs in priority fields are made, tested, and piloted. This overlooks the changes to wellbeing, livability, and civic and social infrastructure that can be introduced as a consequence of innovation projects and pilots. Good places to live and work generate overall better returns and, in the context of mission-driven government, it makes sense that innovation policy and funding should be expected to make a direct contribution to better standards of living for everyone.

For place-based innovation, Labour’s most relevant missions are:

Secure the highest sustained growth in the G7, with good jobs and productivity growth in every part of the country making everyone, not just a few, better off.

Break down the barriers to opportunity at every stage, for every child, by … raising standards everywhere.

A direct focus on good jobs, productivity, and improved standards of living everywhere will represent a pivot for UKRI, whose current strategy sets out the outcomes of innovation in place as happening largely elsewhere — focussed on amplifying the UK’s status as a “global science superpower”, and ensuring that:

The UK’s outstanding institutions, infrastructures, sectors and clusters have positioned the UK as a global leader in R&I [Research and Innovation], with strengths across the UK.

This potential shift from a spillover model to one focussed on delivery creates an important opportunity to reflect on innovation policy. What is the social innovation ecosystem that can and must be put in place to ensure societal benefits match and dovetail with economic opportunity?

AI in the Street

Throughout the AI in the Street pilot, researchers have worked with community partners and artists to situate public engagement with AI in five city streets, examining how AI presents as a messy social reality and asking the question: How can people’s experience inform the governance of AI in cities?

Image taken from a slide deck by Noortje Marres for the AI in the Street show and tell, 05/09/24

This multi-partner pilot has involved four observatories in cities across the UK and another in Logan City in Queensland, Australia, each using different methods to chart the impacts of AI and data-driven technologies on people and their surrounding environments. This pilot phase has combined creative and artistic interventions with qualitative research, participatory workshops and shared observation activities such as sensing and data walks, and group diagramming and mapping.

The observatories have taken place in the context of both designated innovation locations (sometimes called “test beds” and “sandboxes”) and across less formal urban innovation landscapes in locations such as Leith Walk in Edinburgh and Cambridge city centre. Through the observatories, members of the public have shared their experiences of living and working among some of the tangible signs, or externalities, of innovation and they have also spotted and mapped some of the more invisible indicators. To do this, the pilot has drawn on a number of participatory mapping techniques so that,

actors with different kinds of expertise in and relevant experiences of an area of research and innovation are explicitly invited to inform, at designated moments, the process of interpretation in which indicators play a role. [2]

Mapping invisible networks on Leith Walk, Edinburgh - the ‘Black Box’ installation from the Edinburgh Observatory.

The visible externalities range from the fantastical to the mundane and include, but are not limited to, drone delivery systems, automated public and private transport and mobility infrastructure, rubbish bins with sensors, smart doorbells, personalised pricing, facial recognition cameras, loyalty cards, and data-driven advertising billboards. Sometimes these externalities are situated on the edge of visibility — sensors and black boxes that are tucked away in public places — but many of the other impacts of innovation remain truly invisible and inaccessible to people.

Given the scale and potential of the UK’s innovation investment via UKRI — which has just reached £22bn pa, equivalent in size to the “fiscal blackhole” identified by the Chancellor [3] — place-based innovation should be asked to deliver more direct benefits to the people who live and work alongside it.

What does it feel like to live and work in an Innovation Place?

Some of the most striking reflections from the five AI in the Street observatories are on the relationships between innovation and quality of life. How a place “feels” might seem like a subjective, intangible quality, but it is critical to livability, and both the physical infrastructure and behaviour changes created by AI in the street affect the feeling of places in a variety of ways.

One of the most frequent observations made of the impact of AI in the street is that it creates a sense of uncomfortableness and awkwardness, filling public spaces with new kinds of clutter and uncertainty. As one participant who joined a sensing walk in Coventry said,

I can’t take this in as a human, it’s not designed for me.

Flashing LEDs that change colour when people walk past, anonymous cameras that register faces and licence plates, the app-ification of parking, unsupervised delivery robots, vehicles with visible monitoring devices, and the lack of amenities for delivery drivers on shopping streets are just some of social and physical consequences of AI in the street, but these are rarely gathered and examined in a holistic manner.

The Edinburgh observatory saw that the kinds of technologies observed along Leith Walk ranged beyond the usual traffic cameras and payment systems to include a wide range of surveillance tools and monitoring tools, including sensors in rubbish bins, responsive digital advertising, facial recognition cameras, and speech recognition systems. The logics and purposes of these smart systems are well hidden, but their presence is palpable.

The prioritisation of innovation and economic outcomes for smart urban environments also means that their various social impacts are frequently not well planned for or integrated. In Cambridge, for instance, the aim of implementing smart transport infrastructure to create “accessible for all” spaces is undermined by the littering of streets with undocked e-bikes and e-scooters that make pavements inaccessible for disabled people. In Coventry the historic site of Holyhead Road has been equipped with CCTV, ANPR cameras, roadside units and a range of other data capture mechanisms that have been put in place primarily to deliver benefits to the automobile industry, yet no one involved in the pilot has yet spotted any connected or autonomous vehicles actually using the space.

This lack of stewardship extends beyond the presence of street furniture to the manner of integration. The Wings drone delivery trial in Logan worked with local businesses to deliver their goods to a wider catchment area; when it was abruptly cancelled one resident said:

We were very disappointed. It was something that we were proud of doing. It was something different. And then when they took it away from us, it was very disappointing… you made us do all this and we did all this and we accommodated you in every single thing we did. And then for all of a sudden for you to say, well, look, we don't want to deal with you anymore.

This prioritisation of the requirements of technology and technology systems over the needs of people and place is by no means new. Jane Jacobs addressed a similar power imbalance in The Life and Death of Great American Cities. Writing in 1961 she observed:

It is questionable how much of the destruction wrought by automobiles on cities is really a response to transportation and traffic needs, and how much of it is owing to sheer disrespect for other city needs, uses, and functions. [4] (p 353)

Jacobs asserted that policymakers should be able to attain “equilibrium” between the competing needs of people, place, and transport infrastructure, but that — at the time of writing — this balance had not yet come to pass in an American city. Instead, the needs of people and place tended to be “eroded” in favour of vehicles, resulting in places such as LA that were “less lively, less convenient, less compact, less safe, for those who continue to have reason to use it” (p. 367). As Samuel Watling points out in “Escape to the country: What makes a successful New Town?”, this pursuit of equilibrium cannot put ideology before practicality — for instance, geographic constraints and transport realities cannot be wished away. However, the hierarchy of innovation places can mean that convenience for innovation is prioritised above the reality of life and work in place.

Sometimes this hierarchy leads to inconvenience, other times it is glitchy or uncanny. From Lime bikes strewn across pavements on London residential streets to “confused” Waymos in downtown San Francisco that “start honking at each other” in the middle of the night, the externalities of innovation are not always well integrated into society.

News Report from ABC7 News Bay Area: Waymo cars honk at each other throughout the night, disturbing SF neighbors.

Such calls for equilibrium may be considered by some innovation enthusiasts as “Innovation NIMBYism”, but it seems probable that a more balanced approach to innovation investment — one that prioritises and actively improves quality of life and livability in places — is more likely to unlock lasting economic growth than a focus solely on the development of corporate infrastructure and the reputation of research institutions.

Invisible Innovation and Trust

Poor stewardship of innovation in place can also affect people’s trust levels.

Some of the externalities of AI in the street — the sensors, monitors, and cameras — are not easily explained and rationalised to the people who live and work among them. Impenetrable black boxes create distance and ambiguity between people and technologies, contributing to what the researchers on this project have termed AI’s “double invisibility” and lack of explainability. The opaque nature of these AI artefacts can have a damaging effect on public trust — at a time when it needs to be nurtured and restored.

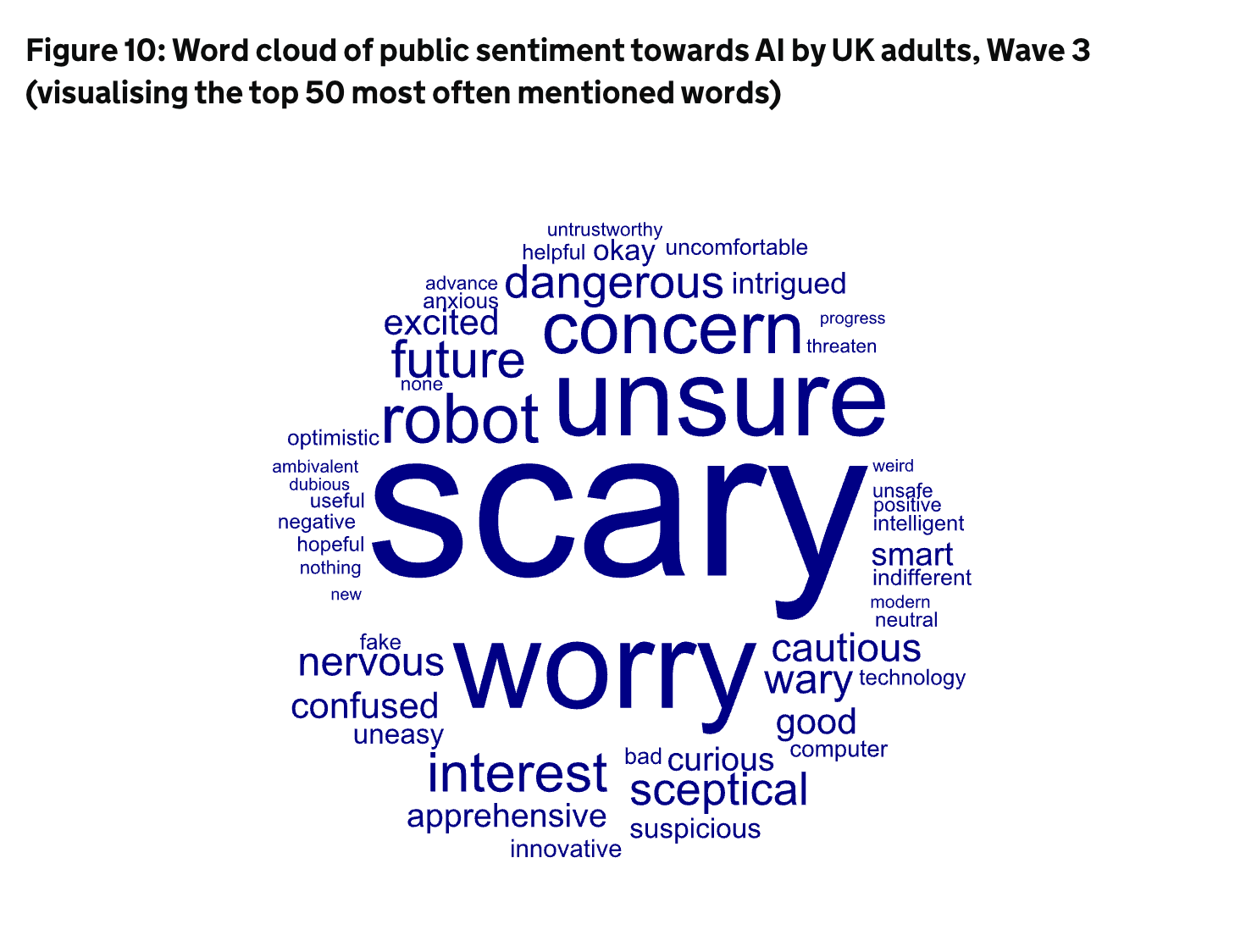

Recent research by DSIT/Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation found that, “the public has mixed attitudes towards AI’s future impact on society, with relatively small proportions adopting extremely positive or negative viewpoints.”

Image from Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, “Public attitudes to data and AI: Tracker survey (Wave 3)”

Polling undertaken in August 2024 by Survation for Careful Industries [5] confirms this uncertainty. At a general population level, people are overall undecided about the impacts that digital technologies have on everyday life; while 43% of people are happy with the trade-offs that come with data-driven digital technologies, 39% are not, and another 19% of people don’t know.

Chart: Public sentiment about the trade-offs around technology, Digital ID in the UK report August 2024

Likewise, a fairly even split of people surveyed express concern about the impact that technologies have on people’s freedoms:

Chart: Public sentiment about freedoms and technology, Digital ID in the UK report, August 2024

This picture looks different when considered across demographic groupings: trust levels in technologies are higher among older people (aged 65+) and people who identified as white than they are in younger people (aged under 54) and people from diverse ethnicities, nationalities, and identities. This demographic segmentation confirms that – for place-based innovation – there is no one-size fits all answer.

Trust issues are exacerbated by the fact that much of the AI found in the street during this pilot does not return a direct benefit to people or communities in place, and it does not address the specific issues those communities care about or want to see addressed.

In their series Townscapes, Tom Kelsey and Michael Kenny reflected on the importance of what they call “civic value” to place:

When public facilities are well-maintained, accessible, attractive and safe, they shape residents’ feelings about the identity, heritage and standing of their town. But when the local pub is shuttered, the park is unkempt and the high street has been hollowed out, the pride of a once close-knit or industrially strong community can give way to pessimism and disenchantment. At the same time, people’s participation in the social, political and civic affairs of their community often depends on the presence of social meeting places. [6]

In the Levelling Up White Paper, Andy Haldane described a similar set of outputs as relating to social capital which, in turn, “amplify the forces of economic agglomeration”, commenting that “Good housing, high streets, and leisure and cultural activities serve as a magnet for skilled people, meaning those places continue to steam ahead”. [7] The tangential nature of much AI in the street — those cables and black boxes that contribute and provide knowledge to other infrastructures, other outcomes — may well reduce the buzz and livability of the cité, prioritising the needs of data and machines over people and communities, and leaving opportunities for social innovations untapped.

The problem of measurement

Can the direct benefits of innovation be measured in a place?

Currently, the benefits of Innovation Places tend to be expressed either in economic terms or considered solely as an output of the innovation ecosystem. This value allocation is reflected in some of the behaviours noted by our Observatories, in which the needs of future innovation are prioritised over the benefits accrued to either people or place.

As Noortje Marres and Sarah de Rijcke point out, a focus only on quantitative indicators may “make society disappear” when the impacts of innovation are measured and assessed on the basis of narrow performance measures. [8] Anthropologist Shannon Mattern discusses the importance of not just surfacing society, but actively accounting for its “messiness” when integrating innovation. Computational frameworks of innovation tend to succumb to the notion that all of “urban life is programmable and subject to rational order”, which can deaden and override existing knowledge and expertise in place. Mattern stresses the need for healthy places to cultivate a “repertoire … of urban intelligences”, that draw on “site-based experience, participant observation, and sensory engagement”.

This preference for plurality is supported by the 2022 paper “Research and Innovation in Place”, written for UKRI by the consultancy SQW, which puts forward an economic theory of change for innovation and place and identifies places where R&I has led to a high Gross Value Added (GVA). This analysis finds that the impact of R&I is higher in places that are already innovation ready, and identifies innovation “stickiness” as being built through a range of pre-existing factors, including,

the diversity and innovativeness of the business base; the strength of collaborative networks (including with other places); the thickness of R&I infrastructure; the capacities/behaviours of key research assets; and workforce skills. (p. 15)

In considering the Sheffield City-Region, the authors find that the opposite is also true, and that socioeconomic factors also have a role in reducing the innovation destiny of a place:

Despite a strong university presence and talent pipeline, wider skills/education, health and deprivation issues [in Sheffield City-Region] are affecting the quality of life. These factors are contributing to … a disconnect between R&I excellence and socio-economic outcomes on the ground. This case study also brings to the fore issues of path dependency and the time it takes to shift place-based economic narratives. (p. 21)

Or, in other words, the presence of innovation is not a magic wand and local spillover effects are not inevitable in a place that is not already economically thriving. A more deliberative approach to stewarding and integrating innovation in place is needed in order to consistently yield rewards.

As Sir Paul Nurse noted in his 2021 review of RDI, “Research, development and innovation (RDI) is an essential driver of productivity and sustainable growth” that has “a critical role in securing economic, societal and strategic benefits”. [9] However, it now also seems clear that a “set and forget” approach to Innovation Places means that prioritising agglomeration over local and regional benefit may contribute to an overall uplift in GDP and innovation reputation, but it cannot be relied upon to deliver practical, noticeable improvements for people in place — which are vital to prove to voters and residents that innovation really works.

This hypothesis needs further investigation, across multiple places, but it seems likely that both more participatory forms and measurement and better integration of R&I with place would not only help to “break down barriers” for participation in innovation, they would also catalyse stickier regional growth.

Funding, stewardship and participation

Rather than a “set and forget” approach to innovation investment that focuses on impacts on the global stage, a more intentional approach to regional innovation could unlock the impacts of innovation in more places. Camden Borough Council has been an early adopter of mission-driven government, and Nick Kimber, Director of Strategy and Design there, has noted their success has been due to localised integration and activation, saying:

The direction is set from above, with missions set by national government, but requiring bottom-up innovation from a variety of actors across the economy and wider public value delivery chain of government, civic society, and trades unions.

In a mission-driven economy, innovation is not an end in itself but a means for delivering change. While the Nurse Review considers the social benefits of innovation to relate only to big social missions such as improving healthcare — taking a trickledown approach to social benefit — the affordances of Innovation Places mean that they could be tasked with nurturing and diffusing the benefits of innovation in more bespoke ways, building on local capabilities to deliver direct benefits and offering more opportunities and agency for people in place.

In his maiden speech as DSIT Secretary of State, Pete Kyle said,

Nothing about change is inevitable. The future of technology is ours to shape, and the opportunities it offers are ours to seize. My ministerial team and I want to see a future where technology enriches the life of every single citizen. (2 September 2024, Hansard)

Taking the opportunity to shape place-based innovation could be transformative for the UK. As this government reassess the role of UKRI and gets to grips with the reality of mission delivery, we propose that a focus on innovation integration and diffusion will be critical to achieving more rapid success.

In particular, we recommend the exploration of the following areas for discovery and further piloting:

Participatory assessment — expanding the notion of “innovation intelligences” to include not only industry partners and researchers, but the people who live and work in Innovation Places. This could be done through introducing participatory, community-focussed measurement and mapping of the qualitative impacts and effects of innovation as a new key performance indicator.

Stewardship — what does “innovation planning” look like and how can innovation in places learn from and be integrated into existing town planning activities? What are the new capabilities needed across local economies and in local authorities to ensure the “delivery chain” of innovation impacts delivers direct benefit to the people who live and work in Innovation Places.

Funding — given the scale of the UKRI budget, what kind of innovation funding would have a more direct impact on quality of life and economic opportunities in places, and how might this be measured? Can place-based innovation funding be recalibrated to deliver direct benefit to people in places, so that the UK’s most important R&I breakthroughs deliver a better quality of life for everyone?

[1] Richard Sennett, Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City (2018)

[3] Research and Development funding policy, “Research Briefing”, House of Commons Library (5 April 2023), Paul Johnson, “The £22bn ‘black hole’ was obvious to anyone who dared to look”, Institute for Fiscal Studies (05 August 2024), https://ifs.org.uk/articles/ps22bn-black-hole-was-obvious-anyone-who-dared-look

[4] Jacobs, The Life and Death of Great American Cities.

[5] Undertaken as part of the Digital ID in the UK project

[6] Kelsey and Kenny, ‘Townscapes 7. The Value of Social Infrastructure’.

[7] Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, ‘Levelling Up: Levelling Up the United Kingdom’., pp. 45-6.

[8] Marres and de Rijcke, ‘From Indicators to Indicating Interdisciplinarity: A Participatory Mapping Methodology for Research Communities in-the-Making’ Quantitative Science Studies, MIT Press. See also, Marres, N. (2024). Do automated vehicle trials test society? Testing mobility futures in the west Midlands. Mobilities, 1-21.

To cite:

Rachel Coldicutt, 2024, Can Innovation Places make good places to live and work?, Careful Industries

Research Findings in Depth: The Observatories

-

Cambridge, UK

What data do disabled people need to move through the street, and how does urban infrastructure interact with the lived experience of access needs?

-

Coventry, UK

How does the AI infrastructure needed for autonomous vehicle trials impact other human and more-than-human users of the street - and how might we see and hear the effects?

-

Edinburgh, UK

Engaging with residents and users of Leith Walk, seeking to capture everyday encounters with AI and understand people’s views of AI’s impact on the street.

-

Logan, AUS

Logan is one of the world’s largest drone delivery trial sites. But what do locals feel about the presence of commercial and autonomous drone delivery systems in their neighbourhood?

-

London, UK

How does AI fulfil expectations, desires and requirements in the street, and what complications does it create? Might innovation emerge from community-driven (rather than industry-led) design?