Jump to the Policy Recommendations | Research Findings

Leith Walk, Edinburgh Observatory

Edinburgh’s everyday AI observatory engaged with residents and users of Leith Walk seeking to capture everyday encounters with AI and understand people’s views of AI’s impact on the street.

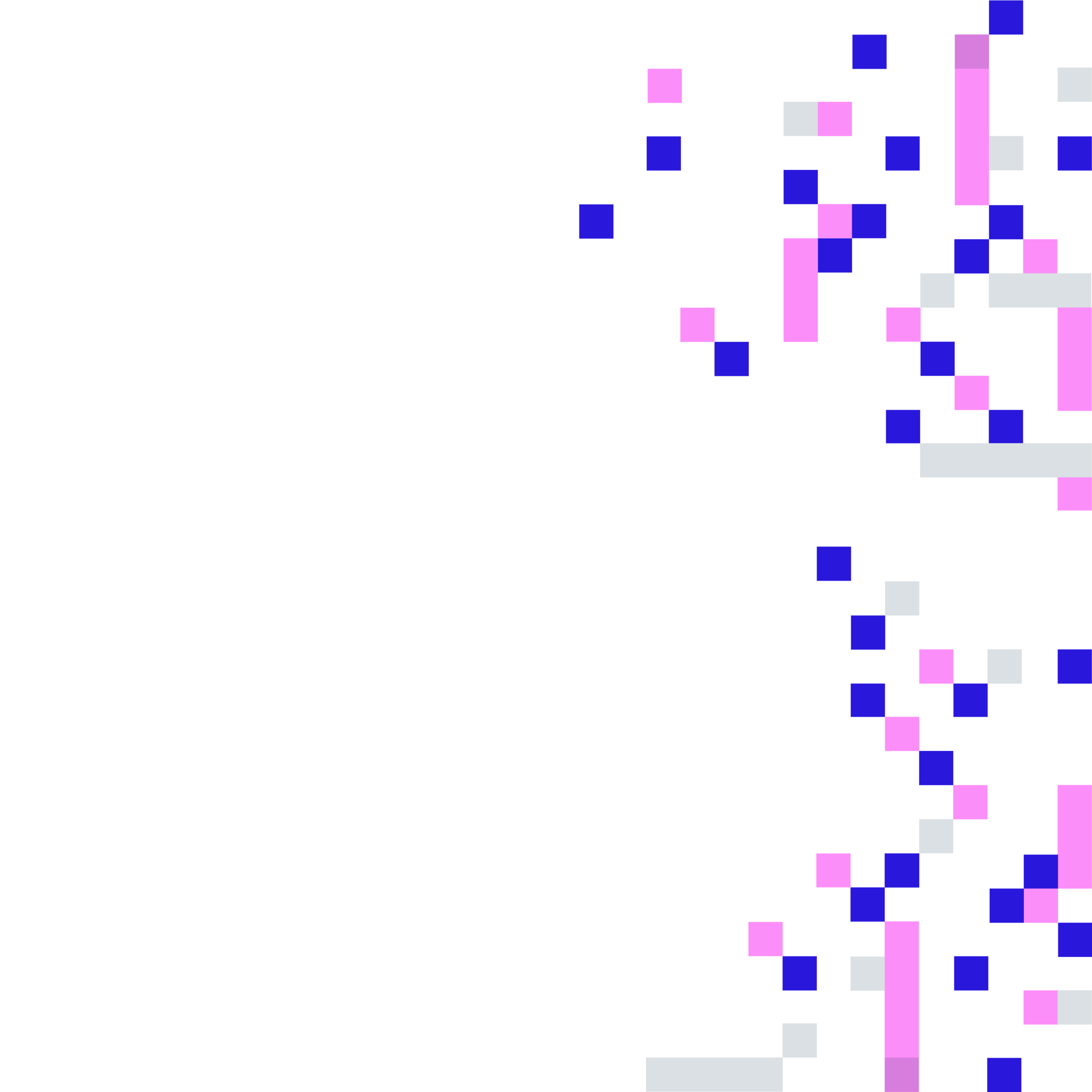

Collage of images featuring the Black Box installation on Leith Walk BY-NC-SAConnecting Infrastructure to Communities, Geographies and Histories

Leith Walk bridges two areas of Edinburgh, and is a site of demographic change. Our observatory explored tensions between impersonal data and the ways humans and AI shape each other in urban spaces.

To engage people on Leith Walk, the observatory used a variety of participatory methods, including “data walks”, prompt cards, a street-based design intervention, etc.

These methods aimed to build a picture of local concerns and the ways in which these relate to a pervasive presence of AI in daily life.

A particular interest was in the ways local communities, geographies and histories connected to AI and data infrastructures—how people might be shaped by these technologies and how they shape the technologies in distinct ways.

For example, Leith Walk bridges two historically divided areas, central Edinburgh and Leith. Through the observatory, concerns were raised about an encroaching gentrification from Edinburgh into Leith and the historically working class Leith loosing its identity. The extractive qualities of AI were seen as a potential contributor to this unwelcome change to the neighbourhood; highly generic data was thought to be informing decisions about the built environment (transport, shops, buildings, etc.) and at a more mundane level, supermarket prices and product availability.

Overall, AI was seen as a threat to interests ‘on the street’ and contributed to a mistrust of private and public sector influence.

“I think we are more prone to adopt anything that is new and that facilitates our way of living. To travel faster, you need the ATM, and things like that. I do understand that some other people want to keep the spirit, the history and everything, the tradition – which is really amazing. But I think it’s a shame it’s really fast; it’s adapting to the new tram, the students, I don’t know, migrants, younger people. I think conflicts are bound to arise.”

– A participant from the group data walk, talking with the group and research team after the walk, expresses a sense of ambivalence regarding technology on the street:

Methodology

The observatory hosted ‘data walks’ with a variety of stakeholders on Leith Walk.

These walks invited local residents, workers, creative professionals, and a Scottish policy advisor to walk through Leith Walk and its surrounding streets, highlighting data- and AI-related points of interest and sharing their opinions of technology’s presence in their environment.

During their walks, we asked data walk participants to take and share photos to a WhatsApp channel, and add short explanations of what they’d taken. This gave us visual and contextual cues for discussions we had after the walks. Broadly, people spoke about the presence of AI on their personal devices, in transport infrastructure and their shopping transactions. They also described how the collection and use of data was having an impact on how people interacted on the street and the sense of local culture.

Edinburgh’s observatory also installed a street intervention on Leith Walk for an afternoon to engage a wider public in discussion. Designed to be an imposing black box, the intervention invited passersby to peer into a narrow slot and view provocative text-based prompts (automatically scrolled through on a small, obscured screen). These prompts were derived from the earlier data walk conversations.

People who engaged with the intervention were asked to write responses to the prompts on paper cards. This intervention engaged a wide and diverse audience, and produced comments that were largely sceptical of data capture and AI.

“It’s one thing to have a camera there, like, as a woman right. You’re sitting at a bus stop. But if you were attacked… no one’s looking at that camera on a regular basis saying I’m going to send help right now. That type of action does not happen. You’re going to look at that camera after the incident happened, after the fact…”

– Another participant from the group data walk captures the way sensing technologies on the street are detached from people’s lived experiences.

Participants

The public body that supports the arts, screen and creative industries across all parts of Scotland on behalf of everyone who lives, works or visits here.

A partnership between The Data Lab and the Scottish Government, tasked with the delivery of the vision outlined in Scotland’s AI Strategy in an open, transparent and collaborative way.

The UK’s innovation hub for traveltech pioneers, working with a community of over 200 traveltech organisations to shape the future of travel, tourism and hospitality.

A pop-up space in a former Police Box which supports budding entrepreneurs, foodies, charities, campaigners, creatives and community groups.

What We Observed

“Those with control of our transactional systems, our informational systems, or political process. We are markets for those with investment in this infrastructure, counted in order to maximise their return on their investment. We are relevant to these processes only to the extent that we contribute to that maximisation.

– Captured during the street-based intervention: hand-written response from a passerby to the question ‘Who decides how you are being counted?’.

Research Findings in Depth: The Observatories

-

Cambridge, UK

What data do disabled people need to move through the street, and how does urban infrastructure interact with the lived experience of access needs?

-

Coventry, UK

How does the AI infrastructure needed for autonomous vehicle trials impact other human and more-than-human users of the street - and how might we see and hear the effects?

-

Edinburgh, UK

Engaging with residents and users of Leith Walk, seeking to capture everyday encounters with AI and understand people’s views of AI’s impact on the street.

-

Logan, AUS

Logan is one of the world’s largest drone delivery trial sites. But what do locals feel about the presence of commercial and autonomous drone delivery systems in their neighbourhood?

-

London, UK

How does AI fulfil expectations, desires and requirements in the street, and what complications does it create? Might innovation emerge from community-driven (rather than industry-led) design?