Jump to the Policy Recommendations | Research Findings

Research Findings

Navigate the key themes and findings of the AI in the Street Observatories.

AI in the Street started with the simple question: what does responsible AI look like from the street?

Through participatory research in 5 cities across the UK and Australia, we explored different ways AI systems impact everyday moments of life in the street. Whilst there are many interpretations of "the street", and different implications for measuring innovation and "publics", the observatories specifically explored publicly owned sites. Using a mix of research-based interventions, from diagramming workshops to sensing walks and access data walks, the observatories explored the presence, roles, and effects of AI-based technologies in the street.

The street is a site of public life — a site where many "publics" converge with different, and often competing, uses and needs. The implementation of AI in the street is often aimed at aiding mobility through space — mobility of people, traffic, goods, money. To this end, the collection of data increasingly becomes required to enable this movement through the street. AI systems simultaneously come to dominate the functioning of the street from behind the scenes, even as on the surface the systems are invisible, and almost irrelevant to how the street is experienced by different publics.

Collectively, the 5 observatories offer insights to how AI innovation manifests as messy social realities and how people's lived experiences can inform the governance of AI in cities:

In the streets, AI is present through proxies. AI systems in the street depend on proxies, such as cars, cameras, drones, or other entities, to function. A high level of technical knowledge is often needed to fully understand how these systems come together to make AI work.

In the streets, AI is doubly invisible: AI tends to function in ways that are difficult to make transparent and they are often designed to be invisible. They often operate beyond the lines of human sight, listening, or observation.

AI is trialled in some streets rather than others. Some areas have become known as "testbeds" or "sandboxes" because they are regularly used as sites to trial new technologies. Existing social, environmental, and infrastructural realities, influence decisions about where to test AI.

In the streets, AI amplifies existing infrastructure and reinforces existing power relations. Innovation is said to be about change, but through AI systems the status quo often becomes further embedded and more difficult to change. In many streets, AI systems are layered on top of existing infrastructure, simultaneously exacerbating and making invisible existing challenges. Through this process, the intensity of technological functioning and operations begin to over-dominate as the street becomes occupied by the tech systems.

In the streets, meaningful purposes for AI can be discovered. There are many existing problems that AI in the street can be seen to alleviate. What innovation enables livable, thriving cities?

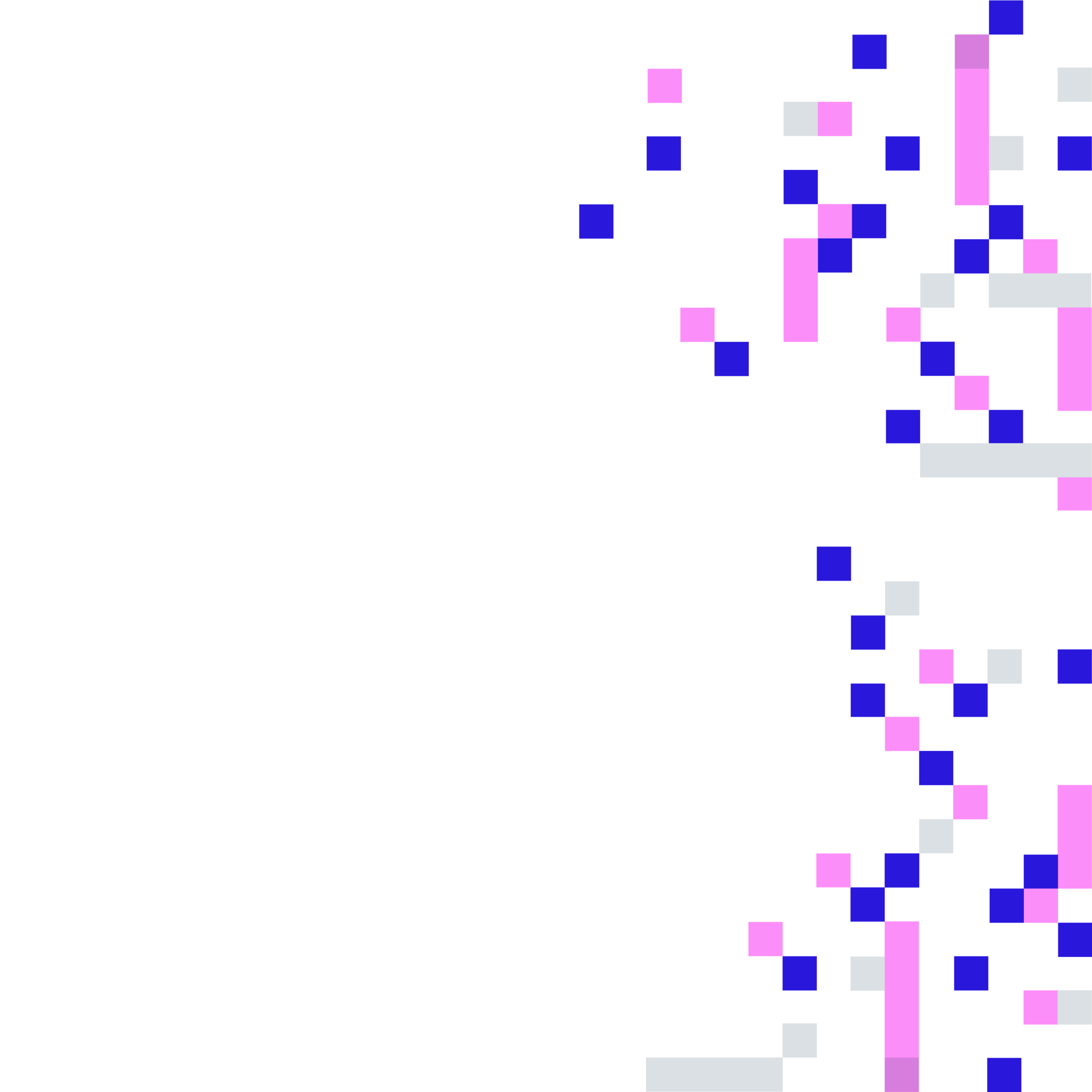

AI systems interact with the street as overlapping and interlocking layers:

the actual street becomes a background layer;

entities such as people, non-human living beings, vehicles, and proxies exist as a separate layer on top of the street; and

the relationships within and between these different entities represent a third layer, interacting in ways that make the AI systems visible or invisible.

We present an exploration of the different layers that make up AI systems as a way to explore the insights that can be gleaned from the messy realities of AI in the street. The layers offer ways to think through the different types of streets AI is implemented, the narratives that are used to justify the roll out of the systems, the common features found in the systems, the outcomes that result from the systems, and future pathways for innovation.

Location Type

What type of street is it?

-

The shopping street is a hub for commercial activity. It is characterised by the presence of entities such as loyalty cards, card readers, electronic transport displays, ATM machines, advertisers, tourists, sole traders, delivery drivers, and locals. The shopping street relies on an intricate web of systems that monitor traffic, public transport, supply and consumption, and people. Such systems aim to optimise every aspect of how the street functions, from supply chains to public services.

The narratives that shape the implementation of AI in the shopping street include:

-

The thoroughfare is the street where many people are in transit — whether to work, to university, to socialise. In the thoroughfare, you are likely to find entities such as e-bike docking stations, cyclists, bus countdown boards, public WiFI infrastructure, vehicle-sensing traffic lights, facial recognition systems, CCTV, workers, students. Many people converge on the thoroughfare, which means there are many types of competing needs interacting on the street. As a transitory location, users share an expectation for optimised traffic flow and ease to get from point A to point B, but they do not hold an attachment to the street since they do not live in the local area.

The narratives that shape the implementation of AI in the thoroughfare include:

-

The commuter road is dominated by the presence of cars, not people. Here you might encounter entities such as SatNavs, planning permission applications, Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras, smart traffic lights and other signage, squashed rats, dandelions, and fumes.

The commuter road indicates an elsewhere and the tensions between technology and the natural environment or between vast amounts of data and local knowledge.

The narratives that shape the implementation of AI in the commuter road include:

-

The urban crossing is where many different users of the street meet. In the urban crossing, entities you find might include pedestrians, traffic lights, e-scooters, wheelchairs, mobile phones, pollards, inexperienced bicycle riders, and blister pavements. The interaction between different needs of the street can cause tensions or create "pinch points" where movement through the crossing is impacted by the allocation of space. The urban crossing is a site where many users are likely to take risks and mitigations. This often leads to "clutter" on the street as different users' needs of the crossing compete. At the crossing, there may also be tensions between the expectations of regulatory frameworks and their ability to manage and curtail tensions between different users' needs and the realities of these interactions in practice.

The narratives that shape the implementation of AI in the town centre include:

-

With the street in the sky, a physical concept of "the street" becomes less important and enables a focus on the drone technology that populates the sky. The entities that shape the street in the sky are local birdlife, drone operators, smartphones and delivery app interfaces, dogs and other domestic pets, and large multinational tech companies. Although separate from the physical street, the street in the sky is shaped by existing highway and road infrastructure and car culture and the needs and limitations of the physical street inform why and how the street in the sky gains importance.

The narratives that shape the implementation of AI in the sky include:

Narratives

What goal is the AI system said to achieve?

-

The safety narrative aims to identify and neutralise different types of risks. In the locations where this narrative was indicated as a reason for implementing AI systems in the street, safety refers to managing the flow of pedestrians and traffic. This raises additional questions about where the sense of safety comes from, how to measure safety, and what makes a street safe and for whom.

This narrative leads to AI features that include:

-

Locations where access shapes the implementation of AI in the street aim to either increase users' access to the street or to goods and services. This includes technology being framed as a way to increase accessibility to the street for disabled people or to enable accessible last mile delivery of small goods. As different users interact on the street, this might lead to competing access needs with no singular solution that is universally applicable. Users' competing needs on the street raise considerations about the relationships between different entities that interact directly or indirectly on the street — what these interactions are, and how these interactions are informed by the street's built environment. Ultimately, this leads to the question: what is the intended use of the street, and what are the potentials and limitations of regulatory frameworks in shaping that intended use.

This narrative leads to AI features that include:

-

The modernisation narrative is characterised by development and economic growth of the street. With modernisation as a goal, the potential for investments into the street is a driving force for rolling out AI. These investments are promised to be found in increased spending by tourists in a popular shopping area, existing companies adopting new business models, or new businesses improving the lives of local residents. The narrative of modernisation might draw optimistic support, particularly in areas that are struggling and looking for change. This narrative might also lead to conflict between existing residents, local authorities, and newcomers to the area.This narrative might also lead to conflict between existing residents, local authorities, and newcomers to the area.

This narrative leads to AI features that include:

-

Efficiency narratives emphasise predictability and optimisation. This might be described as the potential to use data to improve the flow of people down the street, to create safer navigation of roads, or to optimise public services such as transport. Efficiency prioritises turning every action and interaction into a data point that can then be used to predetermine future interactions. This raises questions about the possibility that efforts to increase efficiency might lead to changes in how human agency and human interactions are understood.

This narrative leads to AI features that include:

AI Features

What are the features of the AI system?

-

Visibility describes the extent to which an AI system is noticeable, legible, or traceable. Visibility manifests in two ways on the street: in the way the end user is able to know what the system is doing, and the extent to which the infrastructure that enables the AI system is made present in the street. In some instances, users interact regularly with AI systems but the operations of the system are opaque and thus, without the relevant tools or technical knowledge, users are not aware of how the system works, or that what they are interacting with is part of an AI system. Often, the AI systems are built into the environment of the street. Sometimes, this infrastructure is visible on the street but designed to be ignored; sometimes, it is built beyond sight or other ways to sense. The visibility (or lack thereof) of AI systems is a result of their function and design.

This feature can lead to pathways that include:

-

Monitoring refers to how the AI system collects data. Although all AI systems are engaging in some level of monitoring, each system differs in terms of what is being counted and how that counting is then used. Some AI systems are monitoring and collecting data that has a more immediate use, as with the delivery drones. On the commuter road, observers witnessed numerous cars making U-turns, which they suspected was due to an error on the GPS system. Other systems, such as the Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras are collecting data in real time but the impacts of that collection are not necessarily immediate. The same might be true where an AI system is implemented to collect data about how different users engage with the street to inform future planning but what that data shows and what those plans might be aren't immediately known.

This feature can lead to pathways that include:

-

Communication refers to the extent to which information is shared about an AI system or how information sharing is impacted by the implementation of an AI system. This can refer to how a local authority shares information with the public that an AI system is in use in that particular location, for example, by taping a planning permission application to a lamppost on the street. Communication might also refer to how data collected by an AI system is shared with the public, as with transport or advertising displays. This could also take the form of one technology system sharing information with another technology system such as the GLOSA-enabled traffic light collecting information about vehicles on the commuter road and communicating this information to an unseen system elsewhere. In majority of the locations observed, information sharing was unidirectional or did not allow users on the street to engage back in the knowledge sharing or negotiation, only to receive information or have information about them collected. Some concern was raised about the potential for AI systems to result in decreased human-to-human communication, as every interaction on the street becomes mediated through technology systems. This leads to considerations about how AI systems turn the street into information environments and the difference between the street as a (potential) site of communication environment. This also raises questions about the type of communication that is enabled or hindered by the AI systems, what information is being communicated, from and to whom is the communication happening, and what is the purpose of the communication.

This feature can lead to pathways that include:

-

With transactional systems, engaging with the system might result in immediate impact for the user. This is the case with some of the AI systems found on the shopping street where users' engagement with the AI system is to make a purchase at the supermarket or other shops. Similarly, the drone delivery service in the street in the sky is a transaction in that a user can make a purchase using an app on their phone and receive the item from the drone. Whilst the user might receive some benefit from the transaction if the transactional nature of the system begins to dominate the engagement of the street, this has a negative impact on how users experience and interact with the street.

This feature can lead to pathways that include:

Pathways

What is needed moving forward?

-

Trust shapes how publics engage with and experience the street. As AI is implemented on the street, public trust is eroding. Little visibility of and communication about AI systems leads to a breakdown of trust. As life on the street becomes mediated through AI systems this breakdown in trust compounds with wider dissatisfaction with civic life. The rupturing of public trust towards governance in the civic realm requires more than transparency to remedy. Rebuilding trust will require new approaches to innovation — ones that address specific issues different publics care about and return direct benefit to people in the street.

-

AI is implemented in the street in ways that are disconnected from the specificity of the particular street, its social contexts, and local knowledge. The AI systems function by turning every action and interaction on the street into a data point. Through this process, people become understood not as individuals in all their complexity, but as aggregates, where specificities and complexities of life are removed and street life adopts a forced uniformity. This standardisation occurs within and across the street where everything begins to function and appear the same, regardless of location.

-

AI in the street depends on intricate webs of tools to sense, monitor, and categorise every action and interaction that occurs on the street. Constant surveilling is a fundamental aspect of AI systems. Reactions to this constant surveillance are exacerbated by the lack of visibility of, and communication about the systems. AI in the street creates a sense of being observed for someone or something else, where what is calculated and modelled by the system becomes detached from the street. The street could be a site that enables reciprocity between people and infrastructure to enhance and strengthen the types of relations that form trusting, respectful, and responsible urban spaces.

-

In the same way the function of AI is detached from the street, so too are the benefits. As a place where different publics converge and interact, the street offers unique opportunities for innovation and change. Building on local capabilities and meeting tangible needs beyond convenience, the street could become a site that nurtures and diffuses social and economic benefit directly to communities, expanding agency for people and improving broader civic life.

Research Findings in Depth: The Observatories

-

Cambridge, UK

What data do disabled people need to move through the street, and how does urban infrastructure interact with the lived experience of access needs?

-

Coventry, UK

How does the AI infrastructure needed for autonomous vehicle trials impact other human and more-than-human users of the street - and how might we see and hear the effects?

-

Edinburgh, UK

Engaging with residents and users of Leith Walk, seeking to capture everyday encounters with AI and understand people’s views of AI’s impact on the street.

-

Logan, AUS

Logan is one of the world’s largest drone delivery trial sites. But what do locals feel about the presence of commercial and autonomous drone delivery systems in their neighbourhood?

-

London, UK

How does AI fulfil expectations, desires and requirements in the street, and what complications does it create? Might innovation emerge from community-driven (rather than industry-led) design?

“Because of GPT, AI has become closer to the street. More people have an idea of it now. How to translate this familiarity into an awareness of societal benefits of AI?”

– Calum McDonald, Scottish AI Alliance, AI in the Street project partner